Credit: KJZZ

The act of using shorthand to record events, though it has changed wildly over the years, has existed essentially since the beginning of writing. Court reporting grew with it. Ever since major court proceedings have existed, those involved have wanted a written record for reviewal purposes.

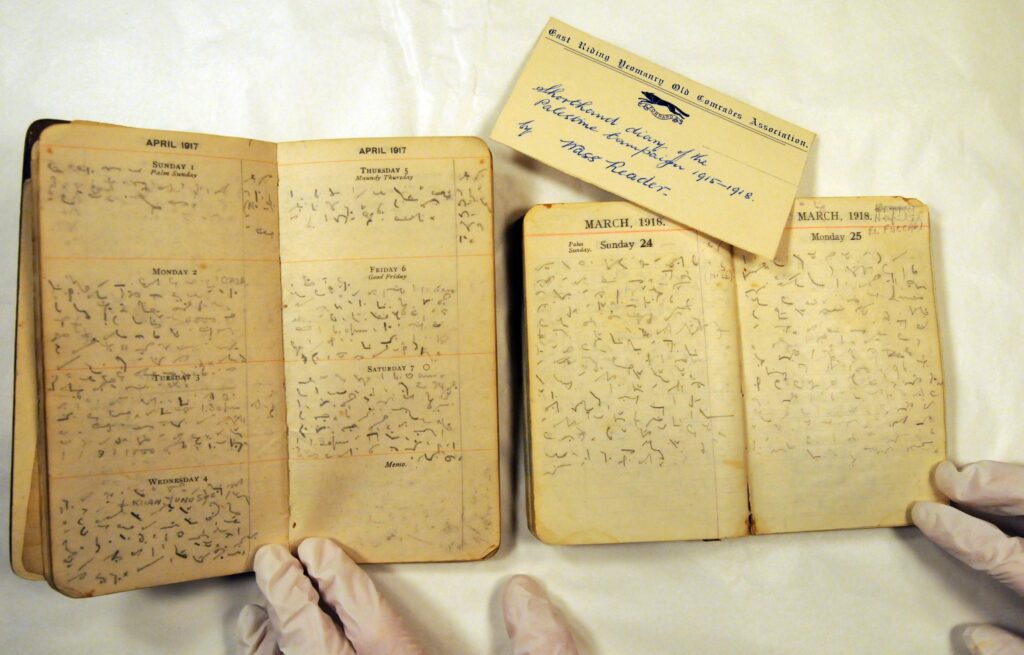

For hundreds of years, court reporters recorded legal proceedings by hand. Shorthand manuals were authored by several different reporters, all of which recorded sounds as signs, symbols, and even shading for faster writing. The most common manual was developed by Sir Isaac Pitman and adapted by his brother, Benn Pitman. Their system was so influential that it could be used by a variety of languages across the world.

Shorthand from WWII. Credit: The History Blog

“Gregg is a way of compressing language,” this piece by The Atlantic says on Gregg Shorthand, a version of written shorthand from the 20 century. “You are the machine that does the encoding and decoding. And your brain can do it in real time at very, very high speeds.”

It wasn’t until 1877 that the first shorthand machine was created by Miles Bartholomew. Ten keys could be depressed at once, which created a series of dots and dashes similar to Morse code. It wasn’t popularized until the end of the century, as other manufacturers started developing their own takes on the shorthand machine.

Since then, the shorthand machine has developed into lighter, easier to handle machinery. But as the years have gone by, some individuals have begun to question the point of hiring a court reporter when recording equipment could easily be used in their place.

An old stenotype. Credit: Johnson County, KS Government.

The fact of the matter is: court reporting and audio recording devices have co-existed for years now, and there is a reason attorneys continue to choose a reporter over a recording device.

The first sound was recorded over 160 years ago—a snippet of a French folk song, “Au Clair de la Lune.” At the time, Édouard-Léon Scott thought he was creating a machine that would make sound waves able to be read visually. It wasn’t until years later, once playback equipment was invented, that researchers realized what Scott had actually achieved. Listen to that recording here:

While it wasn’t the first machine to record sound, Thomas Edison’s “talking machine” in 1877 was the first top record audio and play it back. The talking machine was able to record and play back Morse code, but Edison had bigger ideas. It was later that year and Edison and his machinist, John Kreusi developed the phonograph.

A certain detail here should stick: Edison’s phonograph and Miles Bartholomew’s shorthand machine were created in the same year. Sound recording and court reporting on a shorthand machine have existed the exact same amount of time. With that detail known, if audio recordings are so superior, why didn’t they immediately overtake court reporting?

It’s a trick question: audio recordings are not superior to human touch.

“Lawyers tend to forget that when in court they are making a record, and get lost in the heat of the moment,” says Nate Alder, an attorney in Salt Lake City, Utah. “If you were to go to a deposition, court reporters are always reminding lawyers to speak one at a time. I think the highest level of accuracy is a court reporter slowing everyone down and making sure everyone takes their time.”

Credit: Spectrum News

In theory, it would make sense. Why hire a professional when all you have to do is set up a machine and press “record?” The fact of the matter, however, is that recording devices are not as fool proof as their brands would have you believe. Even if everyone in a court room is in front of a microphone (something that would not only be expensive, but difficult to do without interference), there is no way everything will be properly recorded.

More likely than not, someone will mumble, which will hardly register on an audio device. Doors opening, chairs scraping across the floor, and other sounds could get in the way of what someone says. If someone has an accent, distinguishing what was said over a recording can be difficult at times. Those are only three examples of the innumerable issues that could occur.

Only court reporters can not only properly record what was said and how it was said, but can distinguish between voices. Wherever any of the above problems arises, court reporters step in to solve it. On the occasion a court reporter couldn’t distinguish what was said for any reasons, they can call for a pause and repetition. With just an audio recording, attorneys have no idea what is stated clearly, and what isn’t.

Credit: Hagen Reporting

“Technology has come a long way, but it hasn’t come far enough to put court reporters out of a job,” Michael Pace, president of the National Network Reporting Company (NNRC) says. The NNRC provides attorneys an international database of litigation support professionals. “Attorneys need more than a recording. They need full support throughout the entire legal process. That’s what court reporters can do for them.”

What happens when an attorney requires a transcript of legal proceedings, but all they have is an audio recording? Translation from audio to written word is not yet a reliable mean of production. Court reporters, on the other hand, are able to record, edit, and format the transcript into whatever format their client needs. There is no need to send the audio to a third party and hope they get everything right. The court reporter was there.

On the occasion that an attorney needs a transcription service, however, they can turn to a court reporting firm for that support. Since court reporters are familiar with the often-confusing jargon that comes with law, they can fill in pieces where other transcription professionals might not be able to. Their trained ears and speedy hands can keep up with what was said in court, even if they were not present.

Credit: Amicus Court Reporter

Is court reporting a good career choice? It is an amazing career choice, and I am shocked that we are in a shortage. #courtreporting #nnrc#coulterreportinghttps://t.co/BJZr3JMZIh

— NNRC Court Reporting (@NNRC_Tweets) August 6, 2019

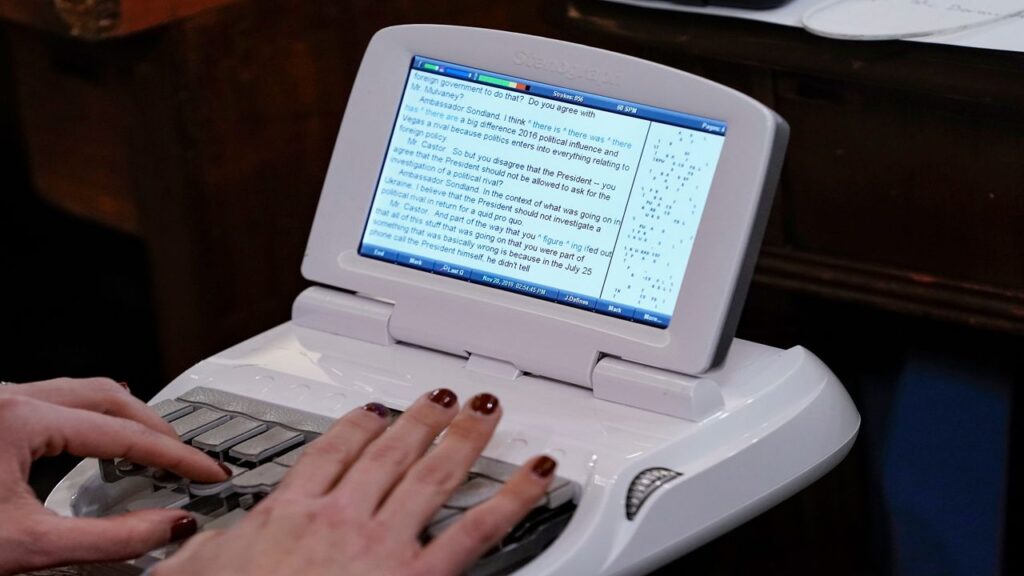

Court reporters can even provide attorneys the instant gratification of an immediate transcript. In addition to their already extensive education, many court reporters go back to get additional certification, such as the Certified Realtime Reporter license. This certification states a court reporter is proficient in realtime court reporting, which is a branch of court reporting that allows attorneys to see exactly what is said as it is being recorded. A shorthand machine is hooked up to a monitor or laptop, on which the transcript is translated into “English” in real time.

At this point, there isn’t any recording device or computer technology that can do what a court reporter does with the same degree of excellence. There is too much margin of error with technology, and attorneys don’t have the time to go back and whatever issues arise. They need a professional who understand the world of law and actually care about providing clients the results they need. A computer doesn’t care if a transcript is riddled with errors. Court reporters do.

To court reporters, their job is a craft. They go the extra mile to educate themselves on the latest in the field. They hone their skills so attorneys have the best experience with their court reporter possible. Once hired, they are part of an attorney’s legal team. They want more than anything to provide attorneys the results they need to form a winning case. That dedication to their clients alone should prove why attorneys continue to use court reporters even to this day.